Cole Hard Facts: Harvard…I’ll pass

Addressing the misconception of prestigious universities attendance leading to greater professional success.

A currently polarizing topic in United States, college admissions have sparked a dialogue whether the university a student attends noticeably contributes to professional success.

March 15, 2019

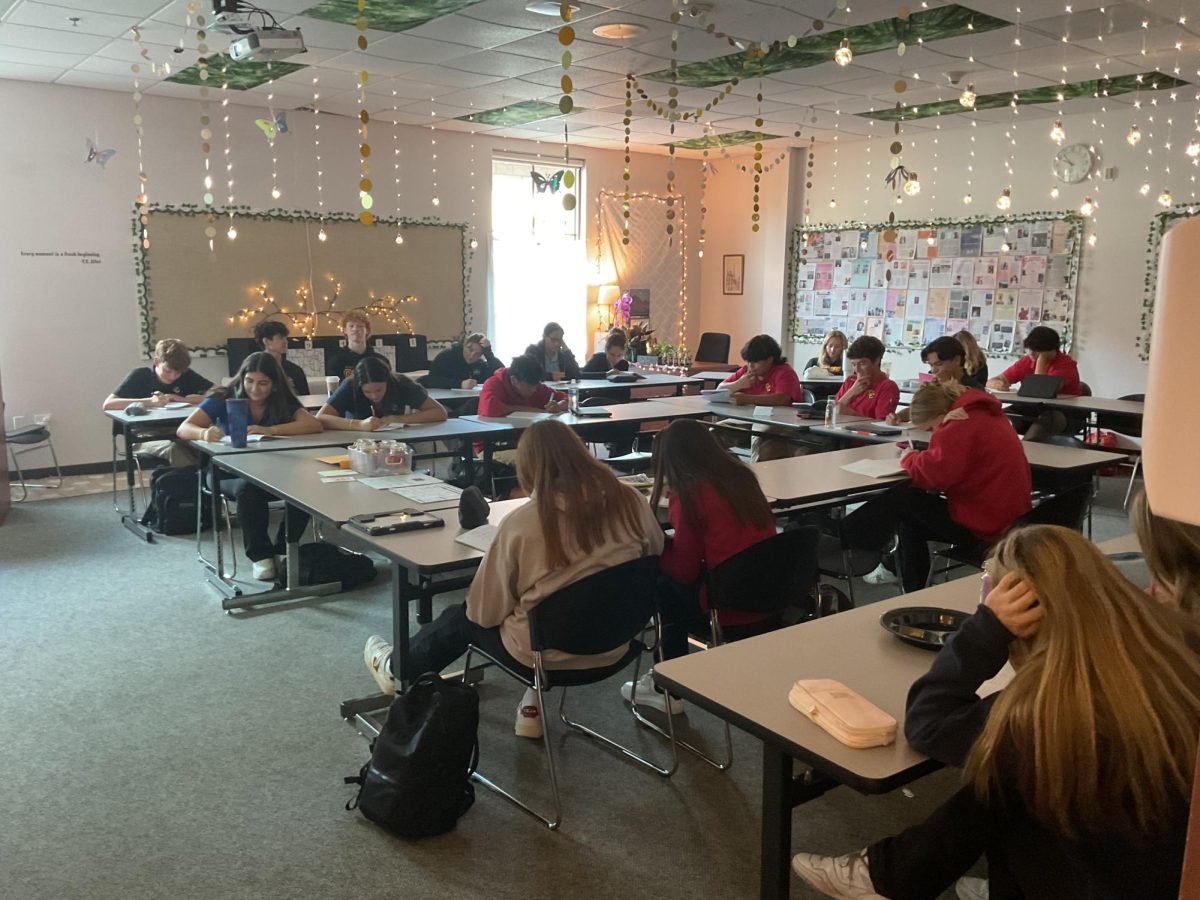

Seven-hundred twenty days of your life making up your high school career are dedicated to an all-encompassing, anxiety-invoking goal: college admission.

However, your own, your classmates’, your siblings’, and your parents’ anxiety, may not be justified.

Studies prove the professional success of an individual has little to do with the university attended, and it correlates much more directly with accomplishments, work experiences, and achievements while attending college. While earning a college degree is crucial, the name listed at the top of the college diploma is where importance falters.

In light of recent events, the topic of college’s pertinence to success is prominent, as an FBI investigation uncovered a scheme by wealthy parents of college applicants cheating the college admissions process through a variety of methods, including having students’ standardized tests corrected by proctors before submission and bribing college coaches to request certain students. Allegedly, some parents paid massive sums to conduct these illegal methods, with a single corrected test ranging from $15,000 to $75,000, according to federal prosecutors.

The extents and consequences of these parents’ choices to allow their children to attend a particular university brings into question the importance of those universities to children’s success.

Researching this subject has proven difficult, as the conditions to properly understand whether a more selective school’s attendance increases graduates’ income are complex. The initial issue in researching the subject rested in the researchers’ belief that the compared graduates fostered similar ability, so the difference in earning cannot be attributed to a deficit in skill.

A study conducted by Stacy Berg Dale of the Mellon Foundation and Alan B. Krueger of Princeton hurdled this issue, as they examined students who were accepted into the same schools, but chose different ones. The students who attended the more selective universities enjoyed no higher income than those students who chose a less selective schools.

Mrs. Dale and Mr. Krueger’s study introduced the “self-revelation model,” which required students to signal their potential ability, motivation, and ambition by their college application behavior. In analysis of the eventual earning of these students, the supposed salary gap between the two different college graduates was nonexistent.

However, if students were adequate enough to get into a selective university but elected to go elsewhere seems discouraging to your cause, Mrs. Dale and Mr. Krueger executed a similarly intriguing study.

In their 2011 study titled Estimating the Return to College Selectivity Over the Career Using Administrative Earnings Data, Mrs. Dale and Mr. Krueger wrote, “We find that the return to college selectivity is sizable for both cohorts in regression models that control for variables commonly observed by researchers, such as student high school GPA and SAT scores. However, when we adjust for unobserved student ability by controlling for the average SAT score of the colleges that students applied to, our estimates of the return to college selectivity fall substantially and are generally indistinguishable from zero.”

In simpler terms, the researchers found, taking in account SAT scores and discounting outliers of nonsensical applications, the students who applied to elite schools and were rejected earned the same average salaries as those students who attended the prestigious schools.

Mrs. Dale and Mr. Krueger’s research is monumental, as it minimizes the importance of attending an elite university and signals hope for students who are entering the mess that is college admissions.

Moreover, these conclusions offer the “pressure cookers of parents” a reason to step back and to consider the actual need for their immense expectations and stresses they hoist onto their children.

Unfortunately, there are counters to some of the aforementioned research, as specified majors prove to pose slight impacts on earnings depending on the school. For example, someone attending a university with a weak business program may not reap the same benefits as someone attending a school with an excellent business department, according to a 2016 Brigham Young University study.

However, there may even be an external explanation to the BYU study’s results, as many great business schools offer internship programs that allow for smoother transitions for its graduates. Complementing this explanation is the fact many other majors see minimal to zero difference in earnings for its graduates dependent on program, according to that same BYU study.

Do not let the previous discussed facts produce doubt in your belief regarding the importance of attending a higher educational institution, as college education correlates with higher pay, job security, healthier behaviors, and more civic involvement, according to College Board, a mission-driven not-for-profit organization that connects students to college success.

Pew Research Center summarizes the crucial nature of attending a college, as it found 77 percent of workers with a post-graduate degree and 60 percent of workers with a bachelor’s degree believe their jobs gives them a sense of identity, versus just 38 percent of those workers with a high school diploma or less. Seventy percent of workers with a bachelor’s degree or more advanced education believe their jobs are careers, opposed to just 39 percent of workers with no college education.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, workers with a bachelor’s degree earn an average of $464 more per week than workers with only a high school diploma.

The overall importance of higher education is different from the importance of attending a prestigious university, as the former proves itself in the real world and the latter does not seem to translate as many people would expect

A healthy interpretation from Mrs. Dale and Mr. Krueger’s aforementioned research could be students should consider selecting a school that meets other vital criteria, such as the school’s sense of community, location, and campus life, and not placing too much emphasis on academic reputation.

The “selective university misconception” has harmful consequences, as it boosts anxiety levels of nearly everyone involved with the college admission process. The process leads students to make poor college choices as they pursue school reputation rather than personal fit, and it leads to many students being unreasonably discouraged during the acceptance letter season.

Ultimately, the college choice of a student is immensely important outside of its academic avenues, as the school will become his or her home away from home, and sprout friendships along with opportunities. One overcoming the discussed misconception will be able to make the most informed and empowered college decision, and it will better his or her chances of attending the school that best fits.

Editor’s note: The views in the column represent the opinions of its author and not those of Cathedral Catholic High School’s administration or El Cid.