Passionate and inspirational English teacher seeks “balance” in retirement

May 26, 2015

A Dartmouth College art museum curator turned high school English teacher and a Cathedral Catholic High School English teacher turned retiree, Mrs. Carolyn Johnson plans to retire at the end of this school year.

After ten years of influencing her students in the educational realm at Cathedral, and previously at University of San Diego High School (Uni) and at Santa Margarita Catholic High School in Orange County, Mrs. Johnson plans to transition out of education to “restore balance to my life,” she said.

“I’m retiring from full-time teaching, but expect that I’ll continue to teach in some capacity – I don’t intend to give it up entirely!” said Mrs. Johnson.

With just one glance at Mrs. Johnson’s extensive and thought-out homework page, one could gather that her disconnect from teaching will be bittersweet. “She teaches from the heart, more than I can manage, I dare say” said Mr. McMurtry, English Department Chair. “Her students are instructed as much in a passionate pursuit of culture as they are in the formalisms of literary study. She approaches literature as a piece of culture and of history, and not separate from them,” he said.

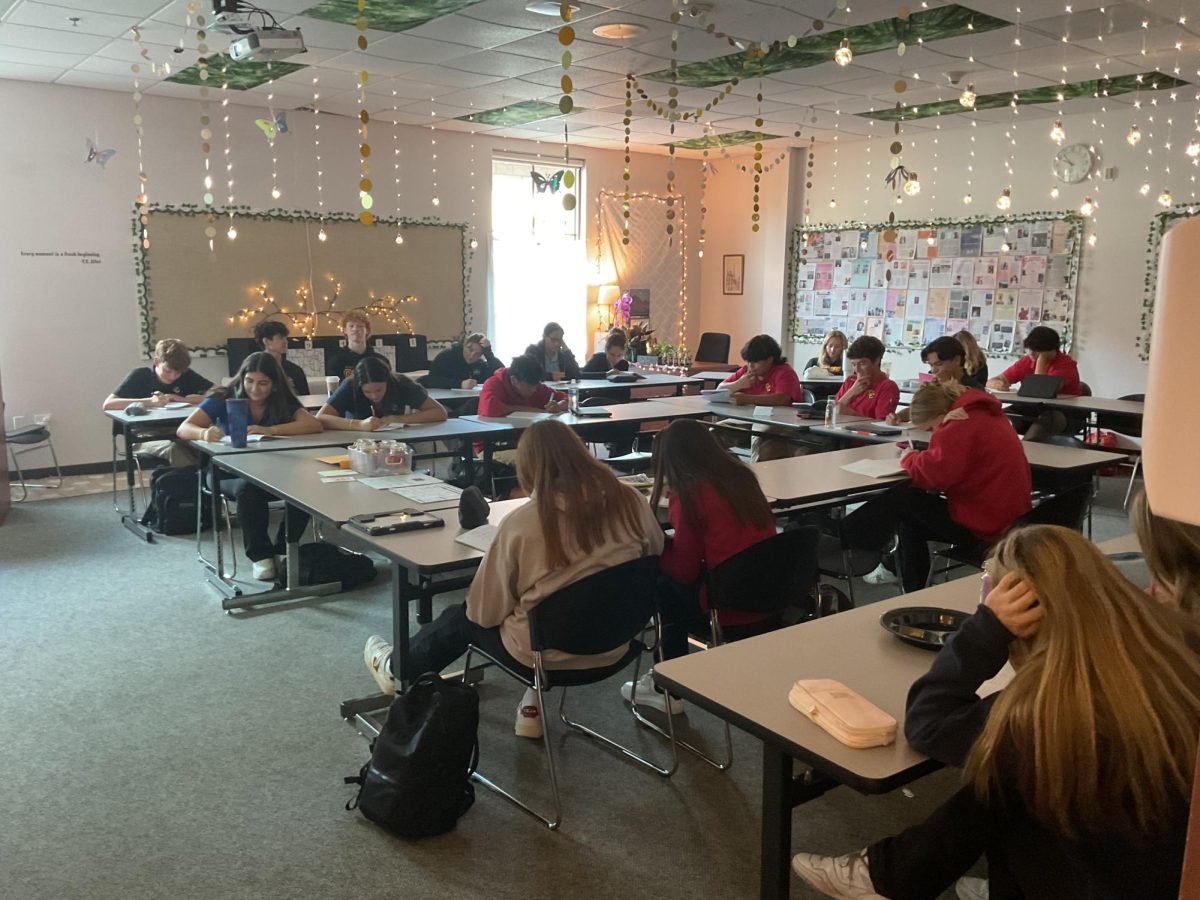

Her passion for teaching in turn enlivens the classroom. Mr. McMurtry said that these passions “make her excellent at inspiring students to dive deeply into a single work. It is hard to inspire this in a student reader, honestly. Students can become impatient. But if done well, and Mrs. Johnson always does it well, the experience is immersive in nature, and quite satisfying. And most students are quite taken with the idea that her classes were not about ‘covering it all,’ superficially perhaps, but about ‘getting into it.'”

Mrs. Johnson’s ability to transfuse culture and ardor into her teaching stems from her genuine fervor for teaching that she discovered when she had a change in course after graduating college. “I was in a demanding curatorial position in the art museum at Dartmouth College, what seemed a dream job for a graduate of art school, but administration was just not for me,” she said. “An English teacher from rural Georgia came to lecture at the college one afternoon, on the project he was doing with high school students to collect stories of their culture and history. I was smitten. I knew I wanted to work with teenagers, at that time in life when they are discovering their unique voices. I wanted help them to hone their writing as a way for that voice to be heard, and to introduce them to the wealth and history of wisdom in stories and poetry,” said Mrs. Johnson.

An educational position of work gave Mrs. Johnson an active opportunity to influence the next generation of readers and writers through her work. “In high school I was privileged to have English teachers who demonstrated very real, personal connections to the literature they taught. I will never forget my ‘American lit.’ teacher, Mrs. Lane, tearing up over a passage in The Scarlet Letter. I remember thinking, ‘there’s a secret treasure in literature from the past, and I want to find it!’” she said.

The idea of finding her own place in academia as a teacher not only came to her during her time spent at Dartmouth, but many years before she even knew she wanted to devote her life to helping teenagers unearth the mysticality of literature.

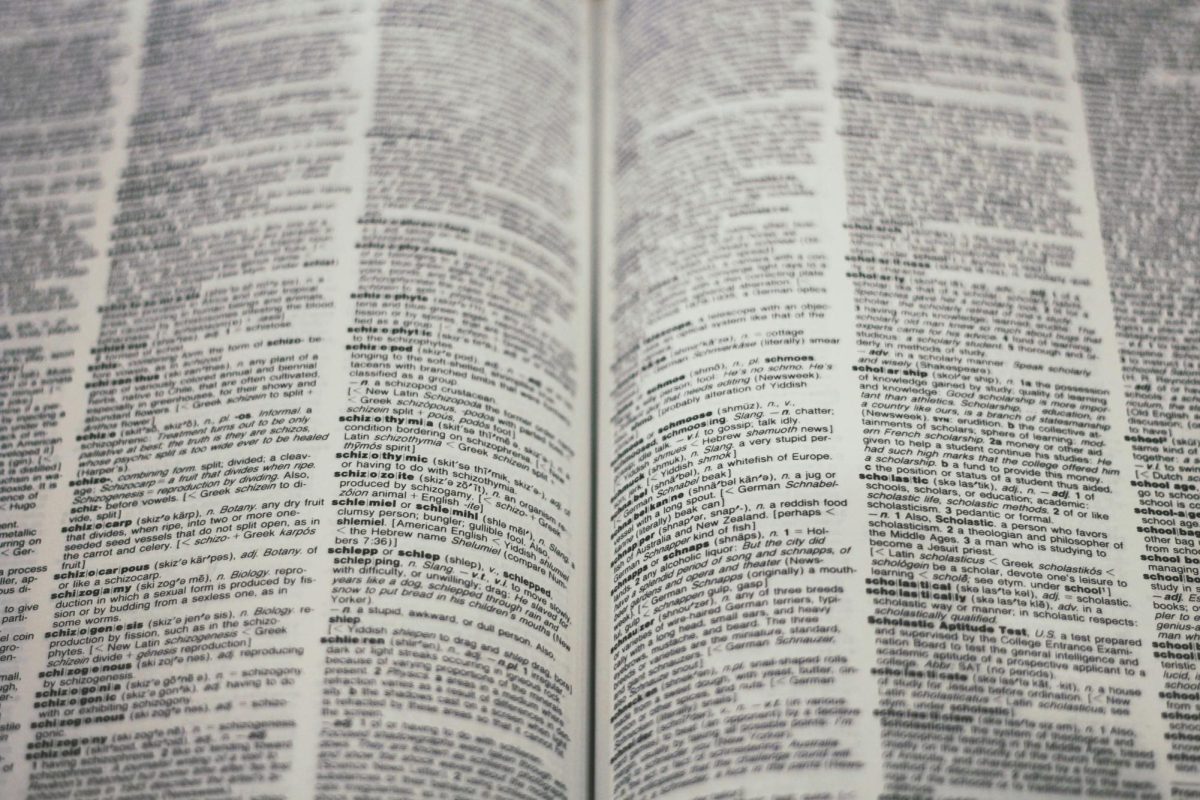

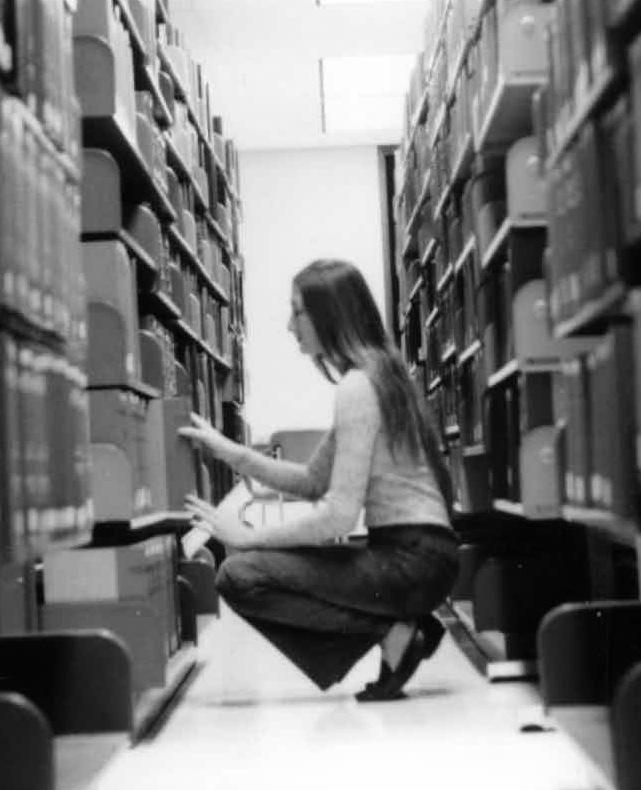

“My mother took me to the public library me every Saturday, and I would leave with as many books as I could carry out in my arms. My library card seemed like a magic key to a treasure trove of worlds in books, all for the taking. I set up a little library of my own in the garage, for lending my own books to other kids in the neighborhood. As a college student, I prided myself in how fast I could get from the card catalog to a source in any journal stored in the depths of the library,” said Mrs. Johnson.

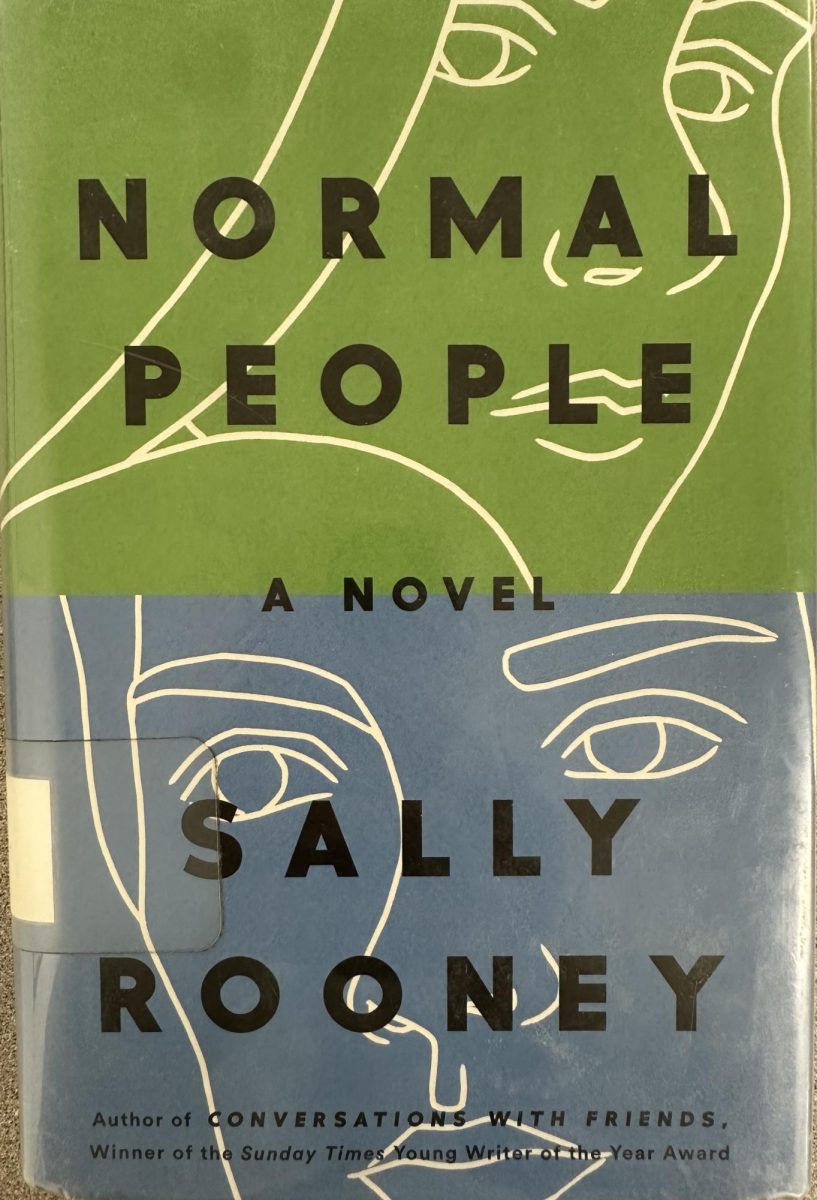

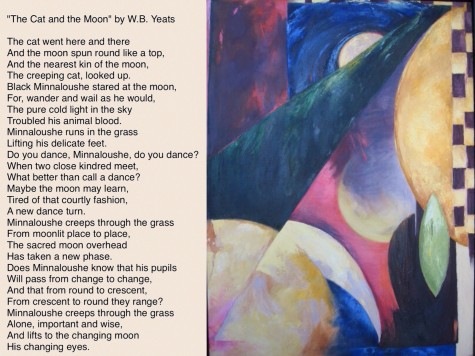

Her days immersing herself into the rich culture books allowed Mrs. Johnson to pinpoint a few of her treasured favorites. “If I had to stand up for one work of literature as an enduring favorite it would be Virginia Woolf’s The Waves. She’s a novelist who turns prose into poetry. Anything she writes sweeps me off my feet,” she said. As for poetry, “a favorite poem is “The Cat and the Moon” by William Butler Yeats. That poem is so magical and musical. I recited it to my son when he was a child, and I made a painting of it for him,” said Mrs. Johnson.

Shifting out of her classroom, she is bound to miss “those unplanned moments in class when discussion is bubbling over, with students sharing riveting stories and opinions, or when the whole class erupts in laughter over something comical that was read or spoken. I love the communal atmosphere of a classroom, that ‘iPad islands’ can never replicate,” said Mrs. Johnson.

“[I hope] that the rich, multi-dimensional humanity of teacher/student relationships are not undermined in the excitement of adopting technologies in the classroom. Communication is nuanced when students and teachers are occupying the same space face to face, in a classroom. So much is learned from one another that can only be seen and felt in our full physical presence, and ‘togetherness,’” she said.

Mrs. Johnson treasures the traditional way of education, the simple but meaningful power in something as basic as handwriting, a topic she devoted her ‘Ignite’ talk to during a faculty meeting on May eighteenth. She quoted Steve Jobs when she said, “you can’t have technology without the humanities,” explaining the cognitive thinking involved in handwriting, something she perceives has been lost in the expediency of technology.

(You can find the PowerPoint of her ‘Ignite” talk here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B2LZ45Q0UoFqaHZ5YlpQYndLOFU/view?usp=sharing)

Mrs. Johnson’s teaching seeks to bring her students together as one body of learners who thrive as one, not learners isolated from each other on their ‘iPad islands.’ Her philosophy, alike the English poet John Donne in Meditation XVII, stresses that “no man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main…because I am involved in mankind.”