“Valentina Zbar. Six years old. Ukraine…Gregory Shehtman. Seven years old. Ukraine…Florika Liebmann. Ten years old. Hungary. Yehiel Mintzberg. Ten years old. Poland.”

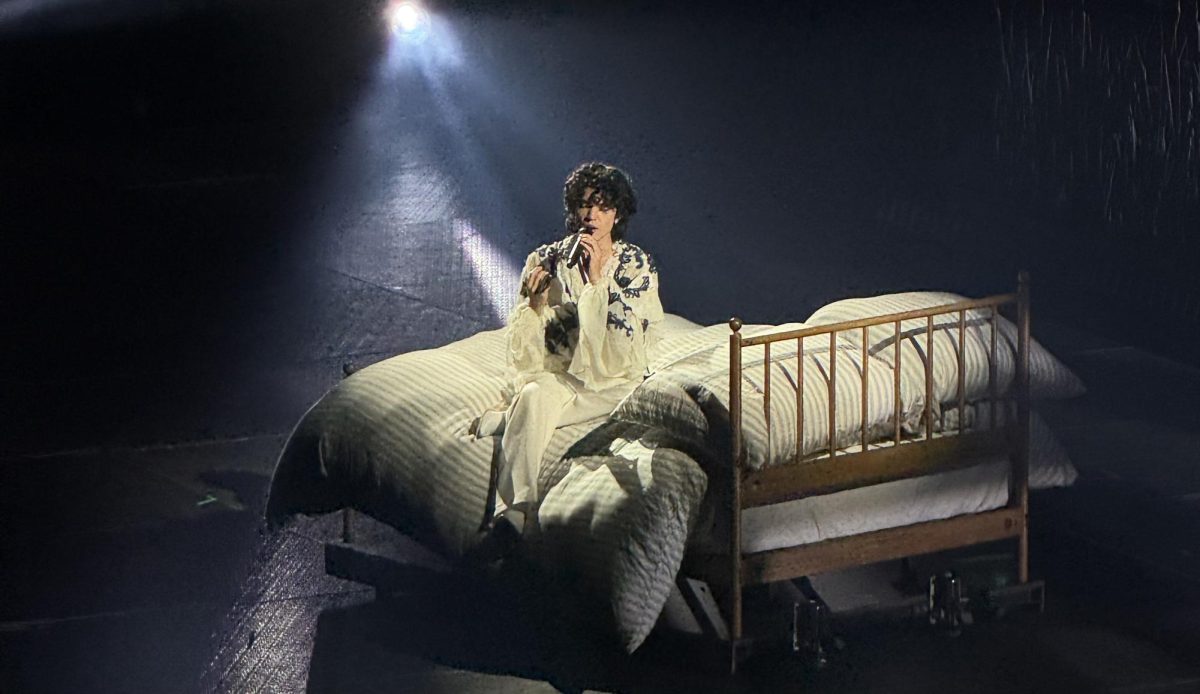

One by one, while walking through the opaque, frigid, underground expanse of a hollowed-out cavern, AP U.S. History teacher, Mr. Don DeAngelo, heard the last, the very last names, ages, and birth places of young children read off by an ominous automated voice.

One by one, in the midst of nothing but lost souls and the impression of millions of shining stars, so richly, brightly, dazzling yellow, Mr. DeAngelo endured only a sampling of the names, ages, and birthplaces of the 1.5 million children that were gruesomely murdered during the Holocaust.

Any distress braved throughout this daunting trek, years ago at the Yad Vashem Children’s Memorial in Israel, was welcomed, however, for without it, an understanding of the horrors these children endured could never be achieved…for without it, the on-campus memorial set to debut this week would not have come to fruition.

As of late, Cathedral has been working in accordance with the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) to develop and maintain the notion that the Holocaust is not a German problem, but rather, it is a human problem.

Together with the National Catholic Educational Association (NCEA), the U.S. Conference of Bishops, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and local dioceses, the ADL eventually developed the Bearing Witness program, which works towards providing Catholic school educators with the resources and training needed to teach students about those who were involved in the Holocaust, the Catholic Church’s role in the peril, the changes the Church has undergone since the 1950’s and the implications of such developments.

After being introduced to the San Diego ADL charter, the program initially encompassed a five-day conference. Now, however, the conference is held every other summer for three days.

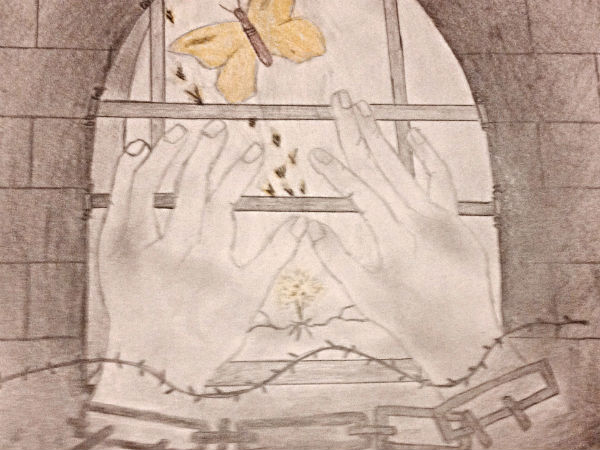

This past year, Spanish and French teacher Mrs. Doina Harrison attended the conference and received the proper training to launch the Butterfly Project at Cathedral. An international project, participants create butterflies that will later be displayed in an exhibit for some of the children lost in the Holocaust.

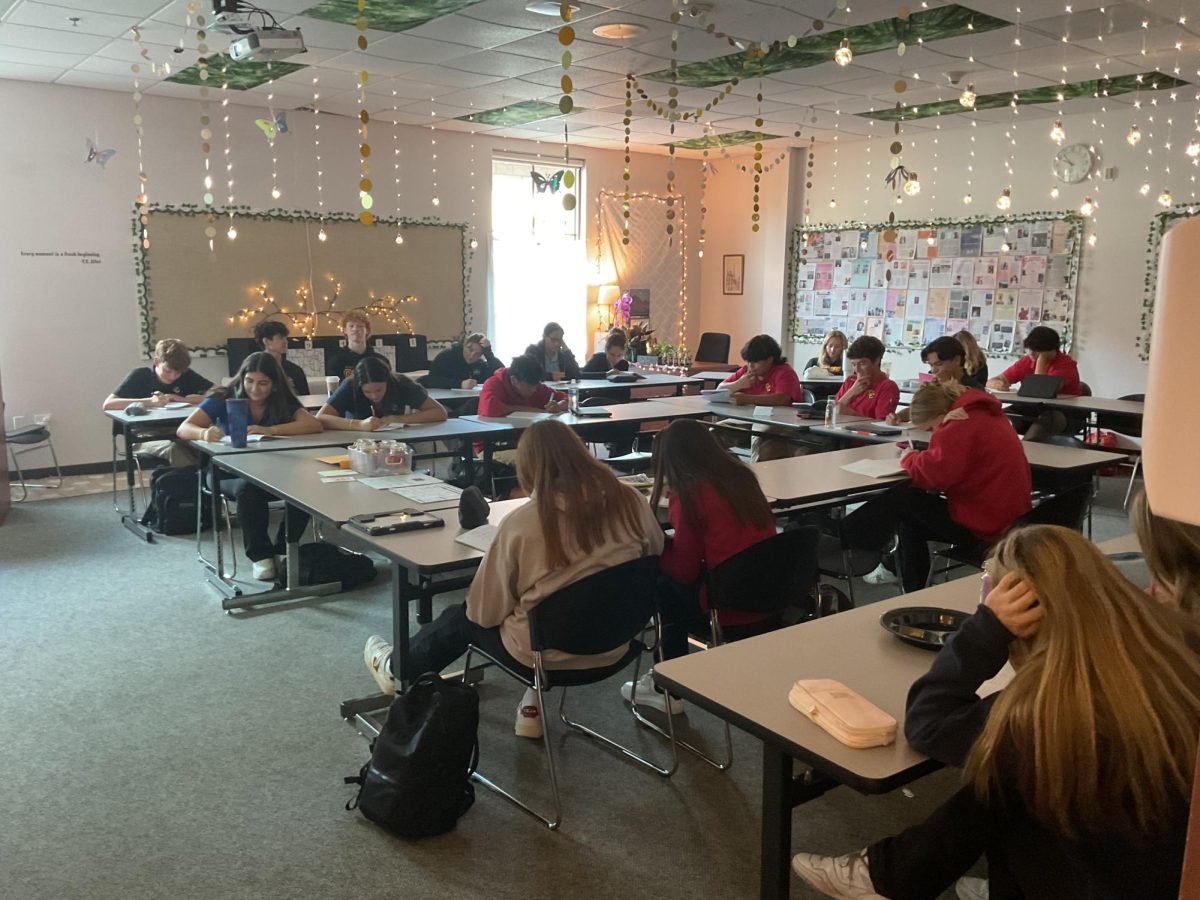

Under the guidance of Mrs. Harrison, French teacher Madame Barbara Chaillou, Art teache, Ms. Silvia Weidmann, 3D Design teacher Ms. Alyssa Vallecorsa, and Mr. DeAngelo, students have been partaking in the project for the past few weeks.

As Mrs. Harrison said, “The only way we can deal with uncomfortable subjects properly is if we talk about them and endure them. By doing this, by taking these small steps, we see what it is that we can do as a society to change perceptions to be tolerant.”

“Being German, the events that happened all those years ago are part of my family’s history,” said German–born art teacher Ms. Sylvia Wiedmann. “From what I’ve gathered from the questions that I have asked my grandparents, oftentimes you’d find that people did not know what was really happening, and oftentimes the new generations do not believe this.”

Despite the fact that the Holocaust is over then, despite the common notion that such mass destruction could never happen again, history is repeating itself.

“[Intolerance] is happening now in the Central African Republic, it’s happening now in Sudan, it’s happening in Syria and Iraq. It’s going crazy,” said Mr. DeAngelo. “It’s not just something that can go away forever, it’s something that can happen at any time and in any place.”

Now, despite the notion that it went away, it would seem that it is the students’ turn to experience only a fragment of the pain these young children endured and to remember the dead.

“I’m sure everyone knows about the atrocities that happened and the history of the events,” said Ms. Wiedmann, “but to see the other side of it, to see that there was a life and to remember that life and celebrate it in someone allows for us to take from this experience something memorable.”

As Mr. DeAngelo said, “It’s a celebration of that child’s memory.”

Thus, after listening to a lecture given by Mr. DeAngelo, each of the students involved in the project was given a biography of a child murdered under such atrocious times. While those in the language department translated the biographies into either Spanish or French, those in the art and 3D design departments have been creating butterflies that embody the essence of the child depicted by their biographies.

“Simply lecturing people on the subject does not make enough of an impact,” said Mrs. Harrison. “Because not only does the project involve people from all faiths, but it also allows students to know, read, and find out about the Holocaust in a really tangible way.”

An artistic interpretation of the stories of those who wished to kiss the world goodbye and who were dragged into a war that went on for over seven years, the 46 butterflies and biographies will be unveiled soon and will remain a permanent fixture on campus for an infinite amount of weeks, with the butterflies residing in the meditation gardens and the book of biographies to be displayed somewhere nearby.

“The students’ reaction to the project has been really positive,” said Ms. Weidmann. “A lot of the students find the project really meaningful and want to be involved. For my classes at least, the project is not worth any class credit, so everything is voluntary.”

“It’s amazing how the kids have really stepped up to the plate,” said Mrs. Harrison. “A major component of this project is the emphasis of the notion that we have to find our humanity, compassion, tolerance, acceptance, and hope. We, in our own little ways, can be the hope for change, and I’ve seen that when my kids police themselves.”

By continuing to integrate the central ideals of this project into the school’s curriculum, teachers are hoping that students will begin to understand that they have the ability to make a difference, even if it is only in very small ways. “Silence is acceptance. Silence means it is ‘OK’ that someone is doing something wrong. Silence means it is ‘OK’ to just not get involved. This is not right,” said Mrs. Harrison, who continued to go on to adamantly encourage students to be proficient and vocal when it comes to maintaining respect among others.

By making students aware that everyone that lived in here during the Holocaust was a potential victim of hate, penned up inside this ghetto, and that death was not only limited to adults, but in fact many young, innocent people were pulled into such destruction when rage ran rampant, teachers are attempting to get students to realize that once hate gets unleashed, it sweeps up many innocent victims.

“The longer hate goes unchecked and the more violent it becomes, the more difficult it is to remove it,” said Mr. DeAngelo.

The latter proves to be especially true when prominent figures are promoting ideologies saying that some life is evidently better than others. As Mr. DeAngelo said, “Once [such notions] become part of the normal thinking and once you imbed that in a society, where does it stop?”

Through the power of word then, through the power of expression, those involved in the project are acknowledging the atrocities that happened and denying anything that limits their responses to intolerant acts. “By turning the situation into something beautiful, we recognize that these were human lives, that these are human lives, when we remember it. Life is sacred,” said Mr. DeAngelo.

Now, it is our turn; our turn to recognize and face such atrocities our turn to recognize that Butterflies Don’t Live Here, In The Ghetto.

The Butterfly

The last, the very last,

So richly, brightly, dazzlingly yellow.

Perhaps if the sun’s tears would sing

Against a white stone…

Such, such a yellow

Is carried lightly ‘way up high.

It went away I’m sure because it wished to

kiss the world goodbye.

For seven weeks I’ve lived here,

Penned up inside this ghetto

But I have found my people here.

The dandelions call to me

And the white chestnut candles in the court.

Only I never saw another butterfly.

That butterfly was the last one.

Butterflies don’t live in here,

In the ghetto.

Pavel Friedmann 4.6.1942