Just one more cookie, right?

Researchers believe excessive snacking impacts many of the same neurological receptors as illicit drugs.

April 14, 2016

Most people know the feeling of reaching their hands into that crinkly, shiny, blue Oreo cookie package and grabbing another cookie, and then another cookie, before stopping and closing the package.

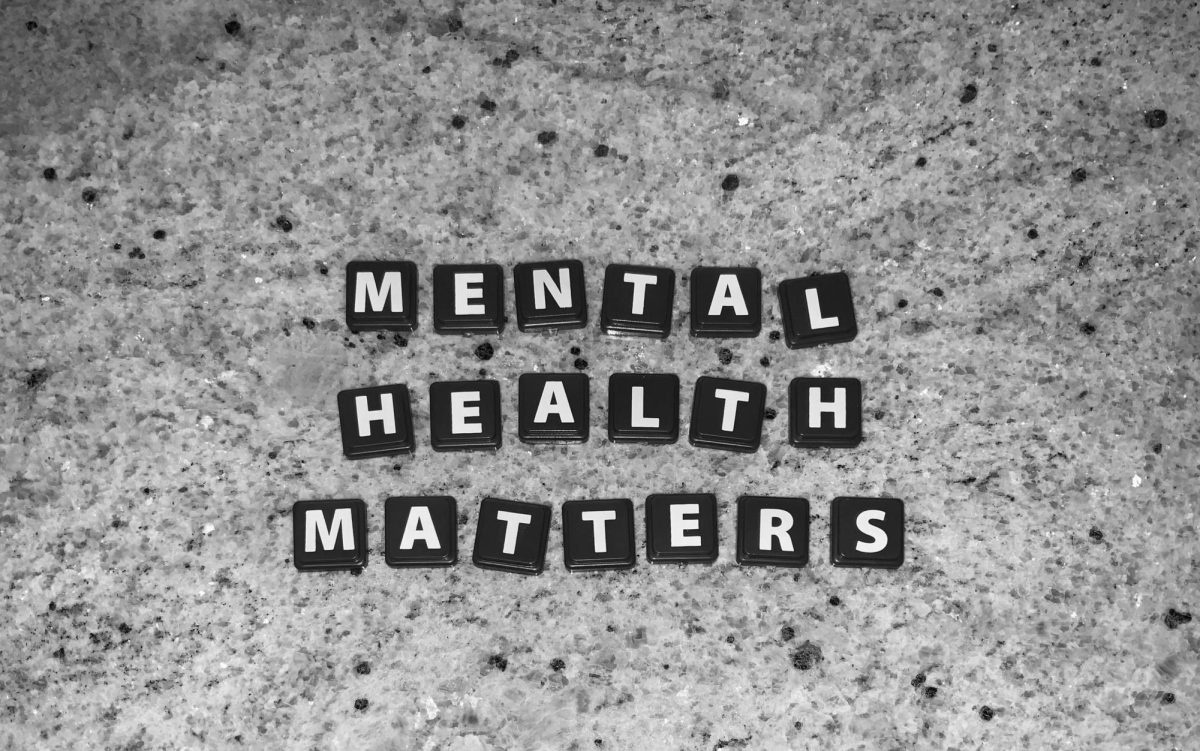

Neurologically speaking, snacking habits, like grabbing another Oreo out of the package, can develop into a larger phenomenon that causes compulsive-like snacking behaviors.

A scientific study conducted by students at Connecticut College in 2013 indicated the addictive nature of some of America’s favorite snacks is comparable to drugs, including cocaine and morphine.

“It may explain why some people can’t resist these foods despite the fact that they know they are bad for them,” Joseph Schroeder, an associate professor of psychology and director of the Behavioral Neuroscience Program at Connecticut College, said.

The researchers concluded that “Oreos activated significantly more neurons” than the drugs in the experiment, which raises the question of whether or not the average human’s snacking habits can turn into a serious addiction?

While this experiment serves as a prime example of how certain foods can affect the reward pathway in the brain, Mr. Francis Caro, a Cathedral Catholic High School advanced placement psychology teacher, explained why the brain reacts to snack foods, like Oreos, and cocaine in a similar, yet vastly different fashion.

“Just because Oreos affect the same part of the brain, it doesn’t mean that it’s the same thing as cocaine,” Mr. Caro said. “I’ve had Oreos before, and I’ve probably had a lot of Oreos at one time; I’ve never become an Oreo addict.

“If I had done the same thing with cocaine, it would have been much harder to get away from it.”

Mr. Caro explained how both cocaine and Oreos “light up” the brain in a similar way. The brain receives pleasure from an unnatural source, such as the artificial and processed sugars in Oreos.

Snacking can develop into a compulsive behavior based on one’s situation. People in today’s fast-paced society often find themselves without time for a sit-down meal, especially in modern American culture.

Snacking is the alternative.

“When people want to eat, they don’t want to make a whole meal and they resort to fast food and snacking,” Mr. Caro said. “It feels good to snack because we’re eating things that taste good to us and it occupies our reward pathway, which makes us feel good in the short run. But, people really snack when they’re bored, which gives them instant gratification.

“When people are stressed, they tend to eat less healthy foods.”

Ultimately, snacking habits reflect the busyness of modern life and people’s range of emotions. While there is a neurological explanation that validates people’s tendency to crave snacks, they are not “off the hook,” Mr. Caro said.

The information also points toward a solution: namely, the need for people to prepare meals. Without mindfulness, everyday eating habits can quickly turn into mindless habits that damage people’s health and well-being.