Rating: 4.7 out of 5.

Viewer Discretion Advised: The review discusses some sexual material and drug use in film; such behavior is not condoned by the writer of said article and should be taken into account for those who decide to view the movie.

In David Fincher’s “Mank,” Gary Oldman’s character states, “You cannot capture a man’s life in two hours, but all you can hope for is to leave the impression of one.”

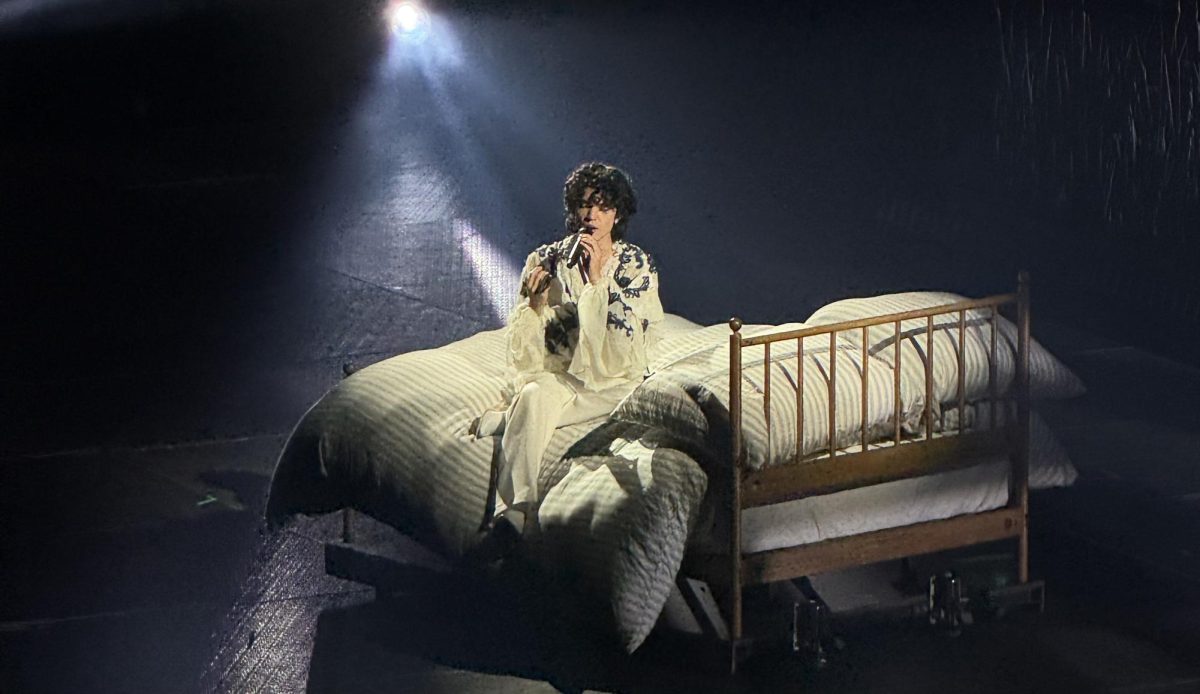

Yet with a behemoth runtime of 3 hrs and 35 minutes with a 13-minute intermission and filmed in VistaVision, “The Brutalist” by auteur Brady Corbet, written with his partner and muse Mona Fastvold, gives no question of a complete story told. On the heels of ten Academy Award nominations and three Golden Globe wins, Adrien Brody, as Brutalist architect Laszlo Toth, shines in this story that reveals the twisted reality that was and still is the American dream.

But don’t let the long runtime intimidate you. The pacing is as flawless as the cinematography.

The story of the film is about Holocaust survivor and former Brutalist style architect Laszlo Toth, who, in his first years after World War 2, migrates to America, briefly meets and is ostracized from his cousin, who has converted to Catholicism with his new American wife.

After a job gone wrong, Toth becomes addicted to heroin caused by the traumas he has experienced from the war, expressed by subtle devices such as the acting and powerful score. But, once Laszlo is at his lowest working in the coal mines of Philadelphia after being dumped by his cousin, he gets a shadowy offer from a wealthy industrialist named Harrison (played by Guy Pearce), who is an admirer of his previous work as an architect, to build a gymnasium as a tribute to his mother.

What follows throughout the two acts is a story of a battle of wills that will surely draw comparisons between “There Will Be Blood” but also a seemingly stark portrait of a period when an immigrant has two choices: assimilation or ostracization.

At its core, “The Brutalist” is a tale of ambition, domination, and control. Harrison hopes to control Laszlo’s gifts, which he secretly envies.

In contrast, Laszlo is obsessed with artistic control, which parallels a filmmaker’s obsession with the final cut. He is ill-equipped to handle the relationship with his wife Erzsebet, played by Felicity Jones. Once she is viewed in America as handicapped, it creates a new dynamic in their relationship.

As Brady Corbet said in press tours for the film after its premiere at the Venice Film Festival, “The whole movie is about this idea of possession, and collectors wanting to possess not just the art but the artist,” according to Screen Daily.

One can not only read the film as a metaphor for the struggle of an artist but also as a metaphor for capitalism in the sense of who gets control. The man with the funds or the man who draws the plans?

Yet every masterpiece still has imperfections. “It loses its focus by the end, rushing toward a conclusion that’s presented as a hasty reveal rather than something you want the movie to dwell on,” according to Vulture Magazine.

Some visual elements are unfocused. For one thing, the over-utilization of the drug and love scenes between actors came off as tonally out of place in a movie squared solely in the realism of the 1950s, complete from costume to set design, that even successfully replicated Brutalist architecture of the era set in Pennsylvania.

By having scenes of surrealism in a realistic film, especially in scenes as delicate over sex, one questions whether Corbet intends viewers to leave the scenes with fascination or disgust.

But besides all the huff and puff of the visual elements, this movie affected me more than any other film since the pandemic rocked cinema, partly due the emotional connection I have to the subject matter of assimilation.

One of the reasons for Laszlo’s ostracization from his cousin is his new wife’s influence, fearing that Laszlo will serve as a reminder of the cousin’s Jewish past from which she wants to move away.

My grandfather had to change his name when he came to America from Orion, Bataan, Philippines. He went from Florentino to Tony Pizarro, choosing the name Tony because his favorite actor was Tony Curtis, known for his starring role in the 1958 film “The Defiant Ones.”

After watching this movie, I realize it is more than just changing a name on a document or choosing a new god to worship for acceptance in this land of the free. Changing the identities we form from birth into adulthood is the act of self-mutilation of the soul.

And the more pieces of change there are, the less our uniqueness will remain. Perhaps that idea of assimilation and ostracization fits well with Corbet’s reading of the film as between art and capitalism.

As stated in RogerEbert.com’s review at the end, “Both can be beautiful. Both can be brutal.”