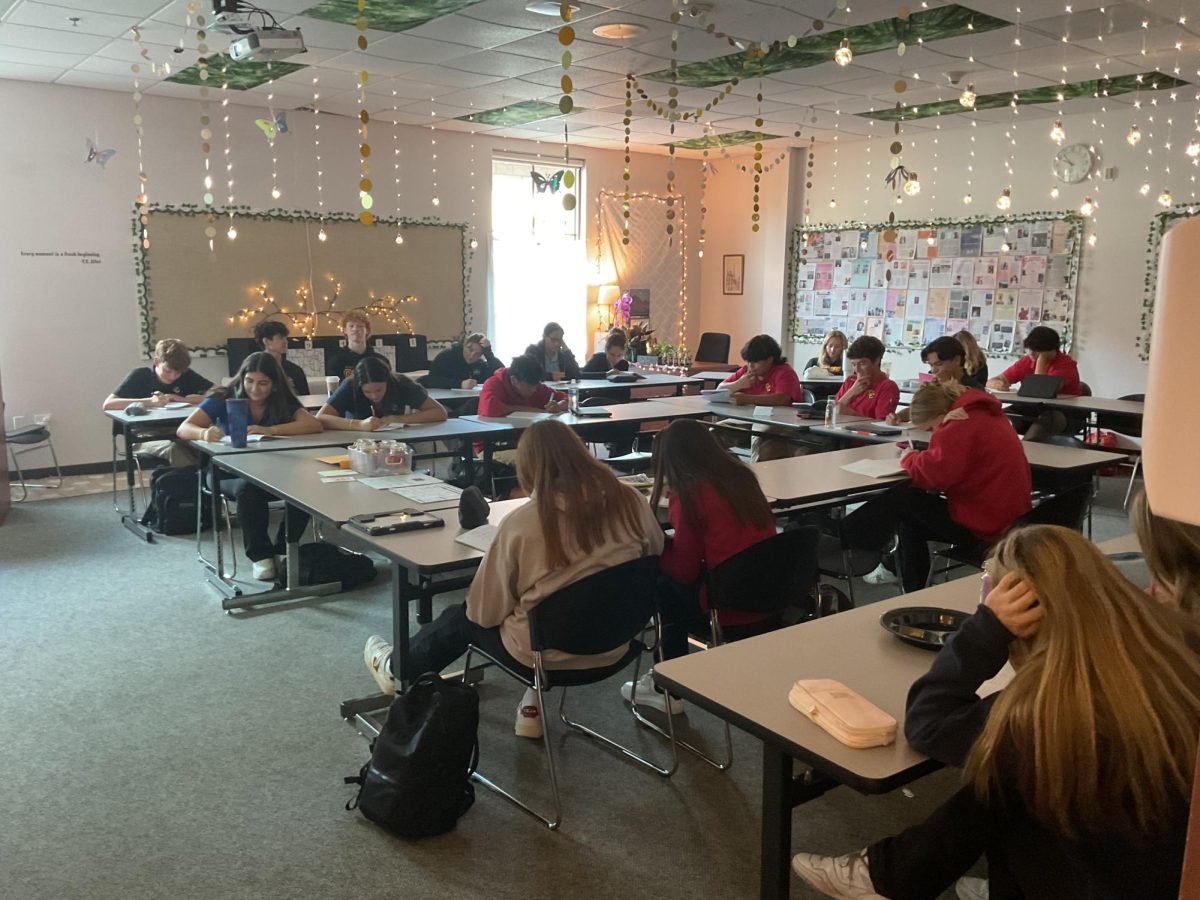

What place does a phone have on a school campus? Should it be stationary on a desk for only teacher use, or in a student’s pocket at their disposal? Should it be treated as personal property that can’t be taken, or as a nuisance that has to be dealt with? For some schools, which may soon become the majority, a phone is nothing more than a pest that, at best, should be kept in a pouch and slipped quietly away for the remainder of the day. This minority of schools has grown to include CCHS this year in a whole new way, and opinions on its impact have become radically skewed in opposite directions.

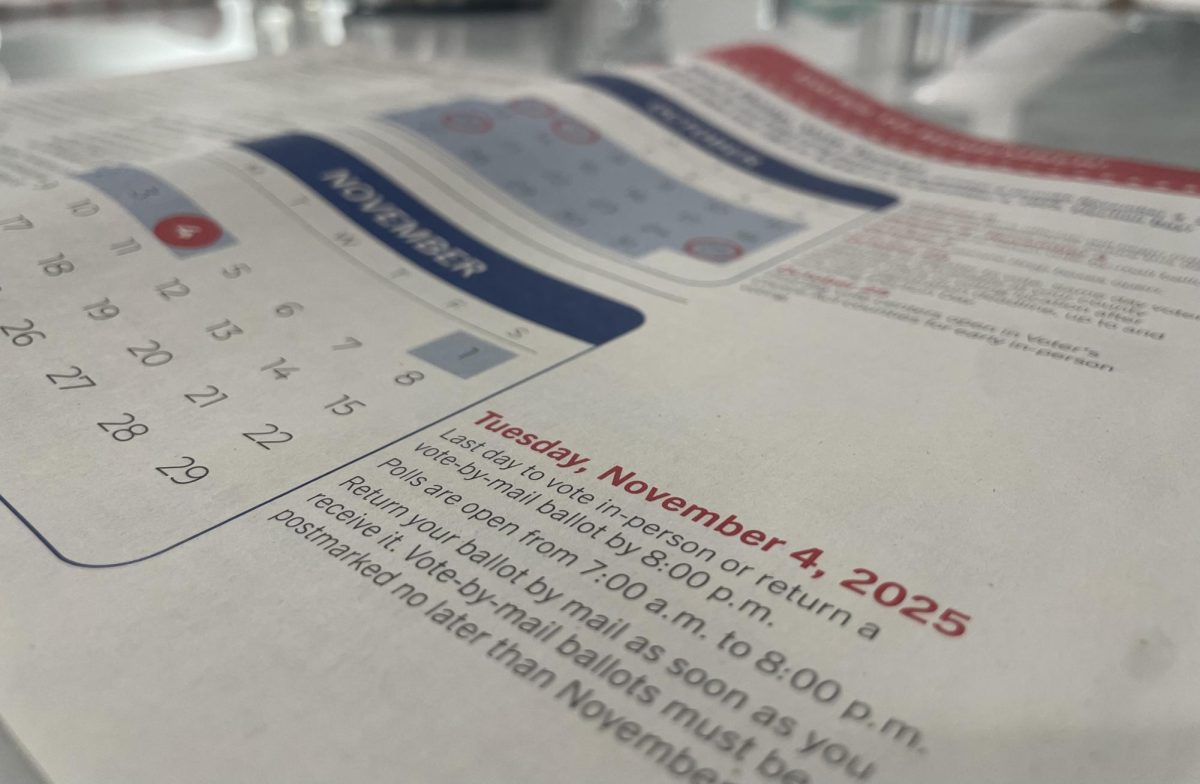

The idea of collecting phones, although fairly new to the current CCHS student, is not new to various school districts throughout the country. Florida was highly scrutinized only last year for proposing banning phone use at school entirely. This idea transformed into a law mandating that phones be taken away during class but allowed at other non-school-related times throughout the day.

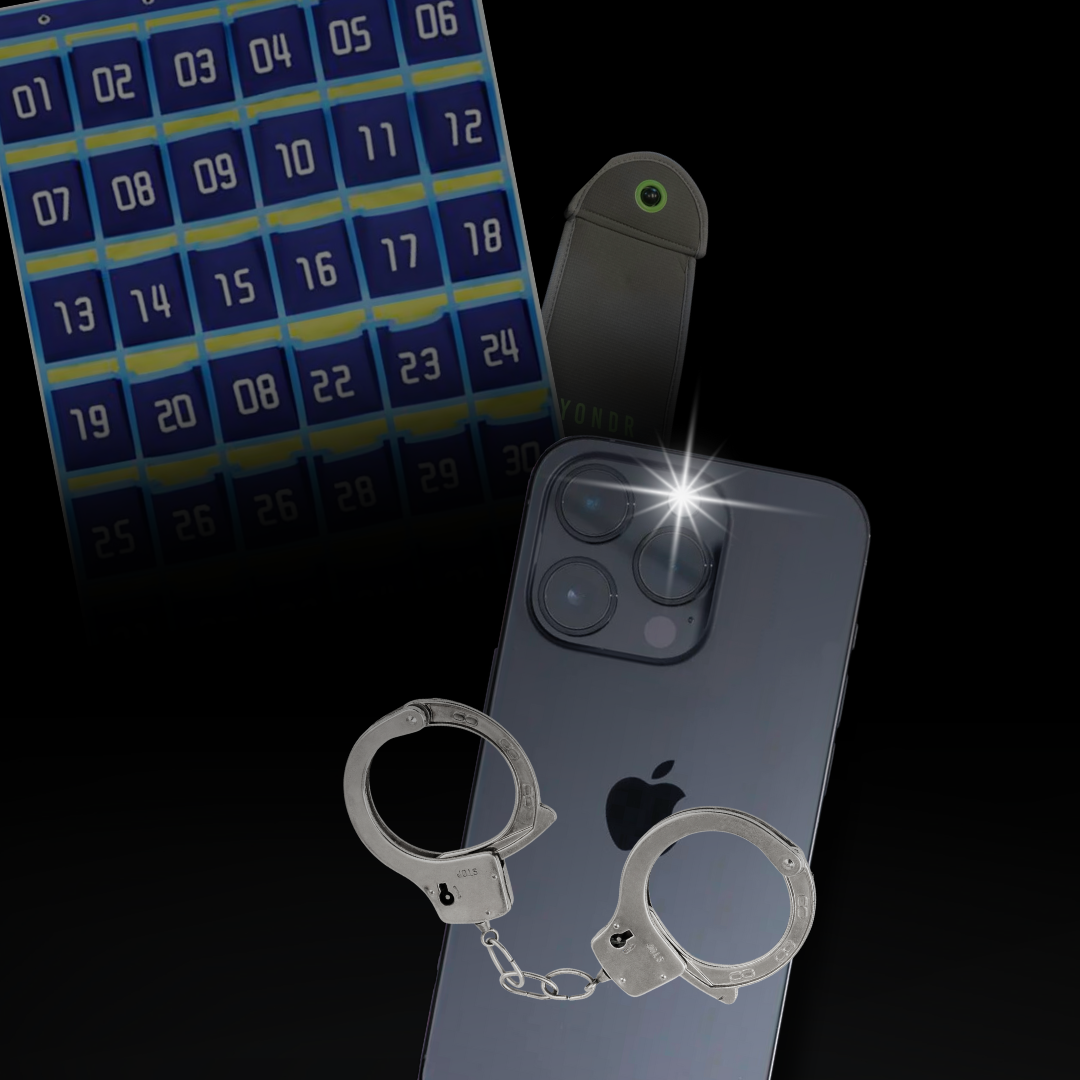

On the other side of the spectrum, and the other side of the country, L.A. Unified School District will enact their recently approved ban starting in January 2025, barring phones not only in class but throughout the entire school day. This system is made possible through a network of “Yondr” pouches that all students must put their phones in for the entirety of the school day. The pouches are then magnetically sealed and cannot be reopened unless with the help of the special machine used to close them. Everything in L.A. Unified’s new system seems as though it would work smoothly, but critique of the policy is severe. How are students supposed to contact their parents? How are they supposed to communicate with friends? In the horrific case of a dangerous event occurring on campus, how would a student be able to contact the authorities for help? It seems as though the benefits of a phone-free school in no way balance out all the cons and glaring issues that come with one.

If this is the case, then shouldn’t the public opinion on the phone policy be the same here at CCHS? Shouldn’t students be voicing aggressive hatred of the policy and demanding a change? Despite what many teachers and administration would assume, that is not entirely the case in the student body. An anonymous survey of 38 CCHS students showed overwhelmingly positive responses compared to what was expected. An anonymous student shared, “It was surprising because we are an ‘iPad’ school, but as a practice I like it.” In that same vein, another student shared, “I wasn’t expecting to, but I actually kind of like it. I feel like I don’t really care what’s going on with my phone during school which is new to me and kind of needed.”

When I first heard about this policy, my first thought was, ‘Wow I can’t believe students who already have good habits are being enforced upon because those without those habits can’t control themselves.’ Some respondents to the survey shared that same thought. “It’s punishment of all for the actions of a few,” said one respondent. “It makes it seem like teachers don’t trust us. I understand the logic behind it but we should be learning self-control instead. In college we’ll have to find a way to pay attention even when our phone is in our pocket,” shared another.

But only a couple weeks into this school year, I found myself realizing that those ‘good habits’ I thought I had were more built up in my head than in reality. I realized that I, despite thinking of myself as some kind of super-focused person, needed this kind of disconnect from my phone. I actually benefited from it. The same was shared by the 85.7% of students in the survey who already considered themselves focused people but still thought of the policy positively.

After a couple of weeks of this practice, students across the board reported more focus. “I like not having my phone on me and being able to feel it in my pocket. It keeps me a little more focused,” cited a surveyed student. As someone who was originally critical, I can corroborate that the subconscious knowledge of my phone in my backpack (and my ability to reach down and secretly check it) kept me from fully zoning in on what I was doing.

“So often in our society, you get a text or a phone call or something, and you feel like you have to address it right away (…) Just because someone texts you doesn’t mean you have to address it right now. And sometimes, it’s a lot better not to,” shares Campus Ministry teacher Mrs. Lonergan who has a much more complex opinion on the topic than just ‘phones are bad.’

It’s notoriously hard for people of all ages to have difficulties when separating themselves from their phones. When I thought of being off my phone, I thought of all the things I’d miss while I was away, all the time I’d waste doing nothing, and all the issues not being able to communicate would cause me, activities that consistently earn me over 7 hours of screen time per day. But after being pushed into having to be off it, I changed my mind.

Of course, there are still outliers. There’s no way a blanket system could cover all kinds of learning styles and needs. For some, doing this makes them feel less connected to what they’re doing and actually holds them back from capturing all the information needed from lectures (taking photos, voice recordings, etc). Of course, some people find a way out of this rule and generally, their choices should not lessen the positive impact it has had. At a high school age, students should have the understanding that their success is their own business, so if they want to go against what they have been advised to do, they can reap the benefits of their choices. That is how good habits are made, through free will, and that is where their choices will lead them.

When asked about the differences between the Cathedral system of collecting phones at the start of each class and more comprehensive policies that ban phones the entire school day, like the one that will be implemented in L.A. Unified schools, Assistant Dean of Students Mr. Duarte explains, “The reason we’re not doing stuff like that is because our school really values self-efficacy. We want Dons to be Dons 24 hours a day. Mr. Threatt and I, we’re not watching you all day (…) we want to prepare our students to be like, here we’re doing what we’re supposed to be doing and out there when there’s just God watching us, we’re doing what we’re supposed to be doing too.”

While on the surface, with the shocking news headlines about Florida’s and L.A.’s phone bans, the idea of collecting phones sounds horrific or infantilizing, in practice here at CCHS, it is something that will continue to build up future generations of Dons, rather than break them down.

Emily • Sep 17, 2024 at 8:24 AM

I like this piece because it shows how a phone policy that seems restrictive at first can actually help students. It’s nice to see this topic from a positive perspective.